By Daniel Dawson Dec. 12, 2022 14:56 UTC

The 2022 olive harvest is in full swing in the northern hemisphere and has been full of surprises.

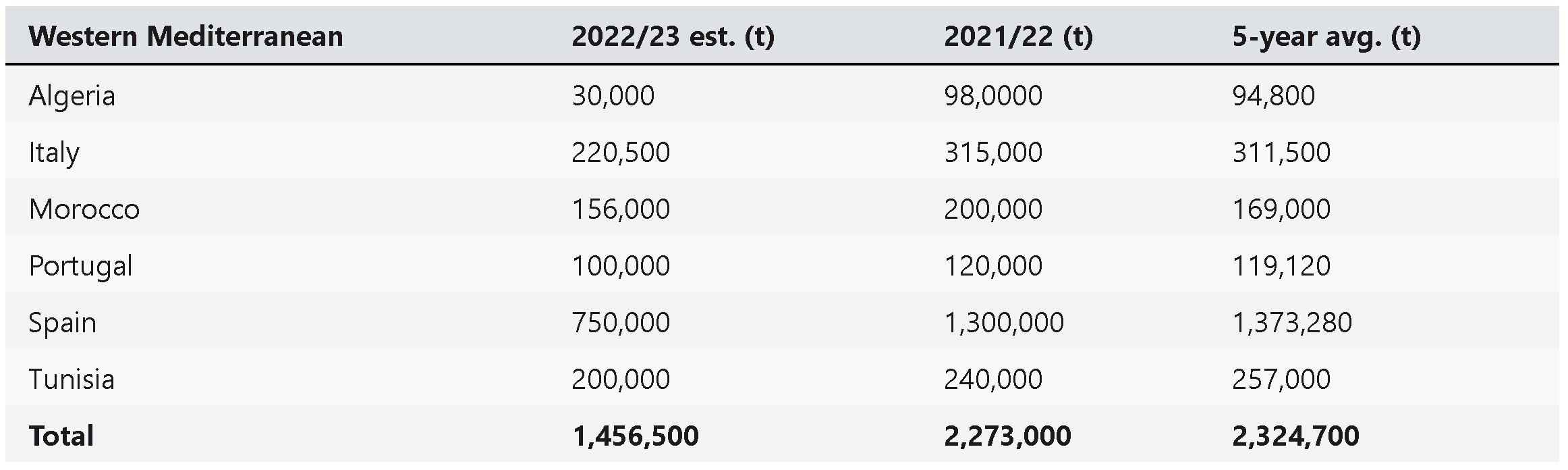

Western European and North African countries that suffered from record-breaking droughts and sweltering heatwaves all have reported substantial production declines.

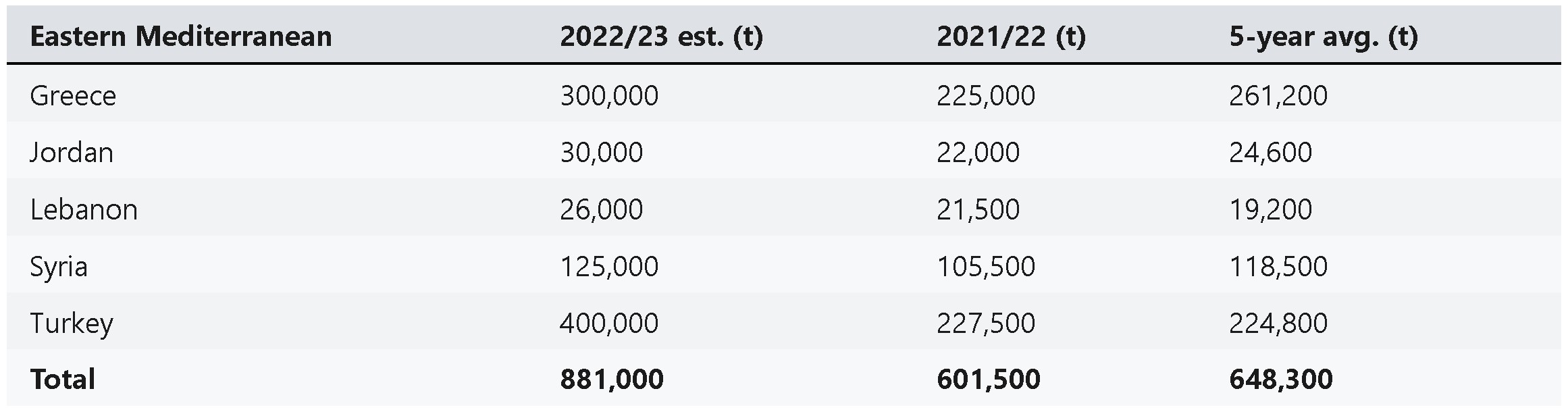

Meanwhile, producers in the Middle East are reporting record-high or near-record harvests, partially attributed to plentiful rainfall at timely moments during olive tree development and mild spring and autumn temperatures.

Easily the biggest surprises of the harvest come from Turkey and Spain. Officials anticipate a record-smashing 400,000-ton harvest in the former, while the latter is set for its lowest harvest in nearly a decade.

Along with eclipsing previous records, this harvest temporarily places Turkey as the second-largest olive oil-producing country behind Spain.

However, Turkey is far from the only country in the Eastern Mediterranean anticipating a bumper crop. Producers in Greece, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine and Syria expect bountiful harvests.

Conversely, on the western end of the basin, producers in Algeria, France, Italy, Morocco, Portugal and Tunisia are similarly bracing for poor harvests.

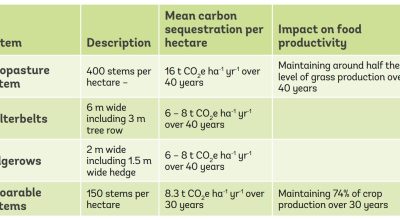

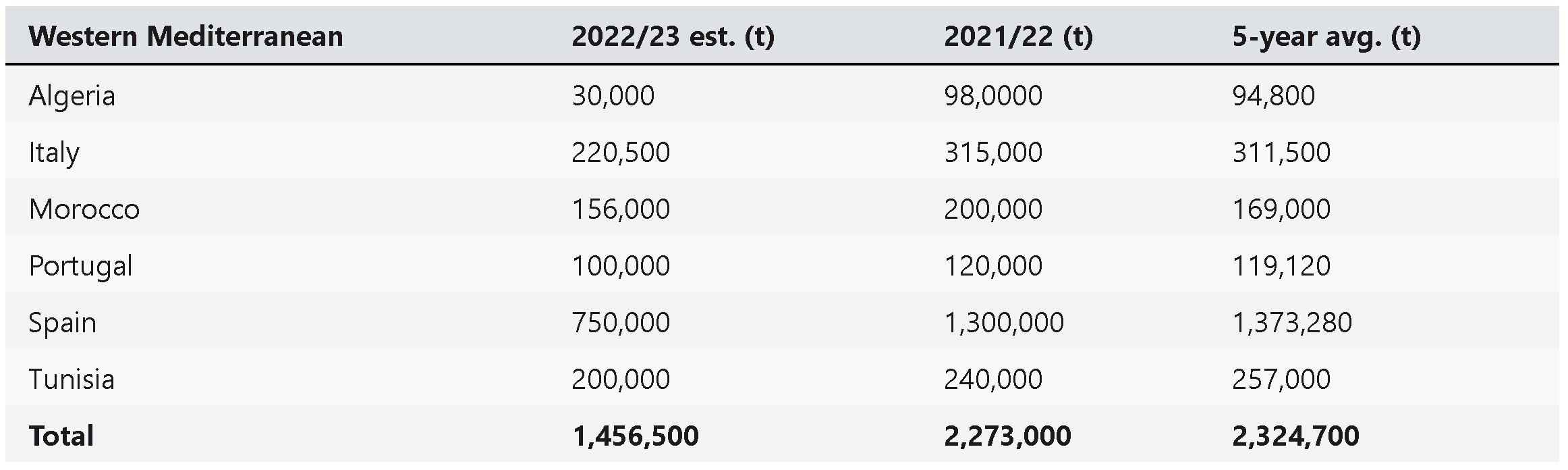

Harvest estimates for the 2022/23 crop year analyzed by Olive Oil Times indicate that production in the Western Mediterranean will be significantly lower than last year and well below the rolling five-year average.

Olive Oil Times estimates that these six countries in the Western Mediterranean might combine to produce 1.46 million tons of olive oil this year, well below the 2.32 million tons produced by the same bloc in 2021/22 and the 2.27-million-ton rolling five-year average.

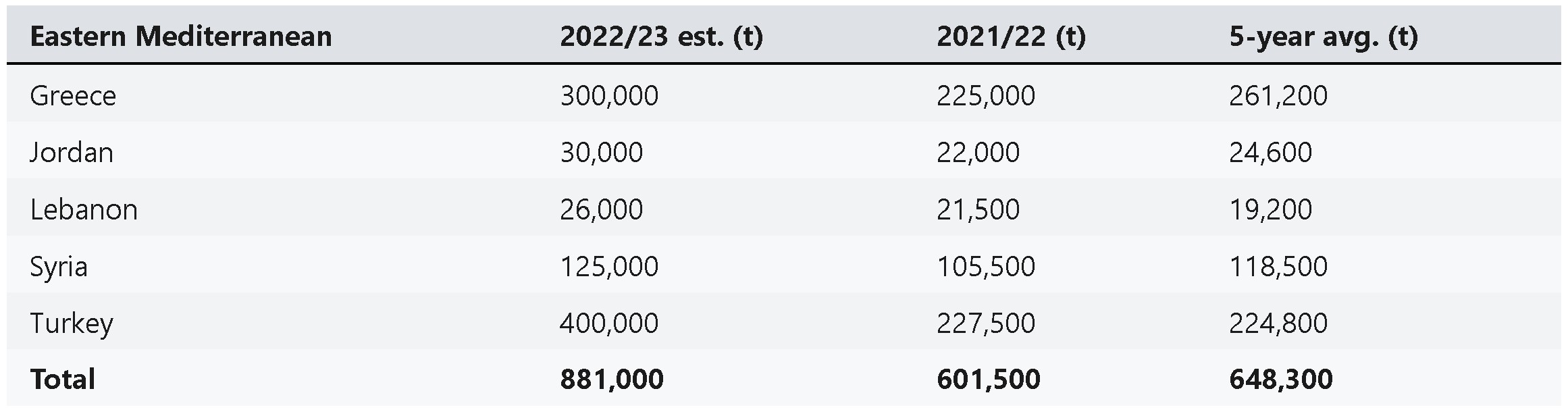

On the other hand, five countries in the Eastern Mediterranean – Greece, Turkey, Lebanon, Jordan and Syria (the latest figures for Israel and Palestine were unavailable at the time of writing) – might combine to produce 881,000 tons in the current crop year.

Conversely, this figure significantly exceeds the 602,000 tons produced in the last crop year and the rolling five-year average of 648,300 tons.

While it may be tempting to conclude that the center of gravity in the olive-growing world is moving east, the reality is a bit more complex.

Experts who monitor global olive oil production believe that this year’s bumper crops across the Eastern Mediterranean and the substantial drop in the west is partially coincidental and partly the result of this year’s unusual climate.

The mild and wet weather in the Eastern Mediterranean that many growers credit with helping olive trees produce abundant fruit is widely considered an anomaly. Overall, the average annual temperature in the Middle East is rising twice as fast as the global average.

According to research from the Italian Agency for New Technologies, Energy and Sustainable Development (ENEA), a 1.8 ºC increase in average global temperatures above the pre-industrial average would result in substantial decreases in Middle Eastern and North African olive production from 2041 to 2050 relative to the 1961 to 1970 average.

On the other hand, production in Turkey and Europe would be far less affected, with some countries projected to experience steady production or even slight increases based on a 1.8 ºC temperature rise scenario.

Advertisement

Water stress is also expected to become worse across the Middle East. According to the World Resources Institute, Israel, Lebanon, Palestine and Jordan are among the six most water-stressed countries and states on Earth.

Many other major Mediterranean olive oil-producing countries are also expected to experience high, though less extreme, levels of water stress.

While olive oil production in Israel, Lebanon, Palestine and Syria is likely to regress to the mean next year when a number of the olive groves in these countries enter an ‘off-year’ in the alternate bearing cycle of the olive tree, Turkey will likely sustain its upward production trend.

Experts partially attributed the country’s record-breaking harvest to sustained efforts to plant 68 to 96 million trees since 2007. This year was the first in which many of these trees entered maturity.

In the Western Mediterranean, temperatures also are expected to rise faster than the global average.

Exorbitantly high temperatures across Western Mediterranean olive groves in May and June damaged some trees during the blossoming phase, resulting in lower fruition levels.

The hot spring was followed by sustained drought. Europe experienced its most severe drought of the past 500 years. Growers in North Africa experienced a similar situation.

Furthermore, water shortages compounded the impacts of the drought and forced many trees to drop or desiccate their olives to save water.

However, meteorologists at AccuWeather, a weather data and technology company, predicted that Portugal, Spain, France, Italy and the Balkan Peninsula would all receive plenty of rain and snow this winter.

While the precipitation is unlikely to eliminate the water deficits created by the drought, olive trees and growers may be in a better position to cope with another hot and dry summer than they were after the abnormally dry winter and spring experienced this year.

Away from the climate, the type of olive groves predominant in each country is also expected to impact production figures.

Western Mediterranean countries, including Portugal and Algeria, are expected to see production rise steadily in the long run due to efforts to plant more trees at higher densities.

High-density (intensive) and super-high-density (super-intensive) olive groves lower production costs and, when managed well, mitigate the impacts of the natural alternate bearing cycle of the olive tree due to consistent pruning and a steady stream of fertigation at the most critical points in tree and drupe development.

As a result, countries with higher percentages of these groves are likely to see steady production increases with fewer climate-related dips and limited effects from ‘off-years.’

The aforementioned ENEA research also indicated that countries with high-density and super-high-density olive groves would see limited production decreases or even modest increases with 1.8 ºC of warming.

Production will likely continue to rise steadily in many Western Mediterranean countries where these types of olive groves are more common.

In the Eastern Mediterranean, Turkey and Egypt (where harvest data was also unavailable for 2022) are the main countries growing olive trees intensively on a large scale.

While Turkey is the exception to long-term olive oil production trends in the Eastern Mediterranean, Italy is similarly an anomaly to Westen Mediterranean production trends.

The unabated spread of Xylella fastidiosa, a deadly olive tree bacteria, and a growing emphasis on quality over quantity have changed the country’s fundamental production paradigm.

Production is likely to recover from this year’s meager yield but is unlikely to reach the heights of the early 2000s when 600,000 tons of olive oil production was the norm.

Based on the prevailing climatic and agricultural trends, the outsized role of Eastern Mediterranean olive oil production compared to the Western Mediterranean appears to be an anomaly in 2022/23.

Indeed, some experts anticipate that organic and traditional olive groves will steadily move north as North Africa and Southern Europe become hotter and drier.

With the heads of France’s leading champagne houses buying land in the south of England, it may not be long before leading olive oil producers begin to follow suit.

Fonte: Olive Oil Times

Caption: Not indicated.